ICFPC 2019: Lambda Coins / Sweeping the Maze

This year was about finding the optimal path in 2d maze that covers all the cells.

This was my 10-th year participating in ICFPC. Below are some of my random thoughts and screenshots.

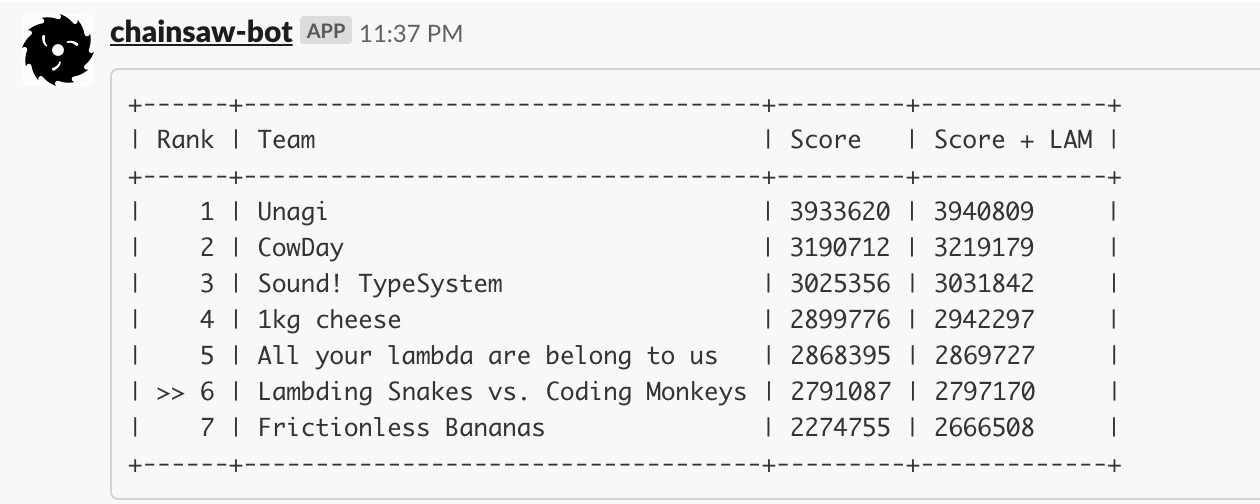

Results

Lightning

At the time of writing the lightning results without top15 were released and now we know for sure, we’ve got 16th place in lightning round:

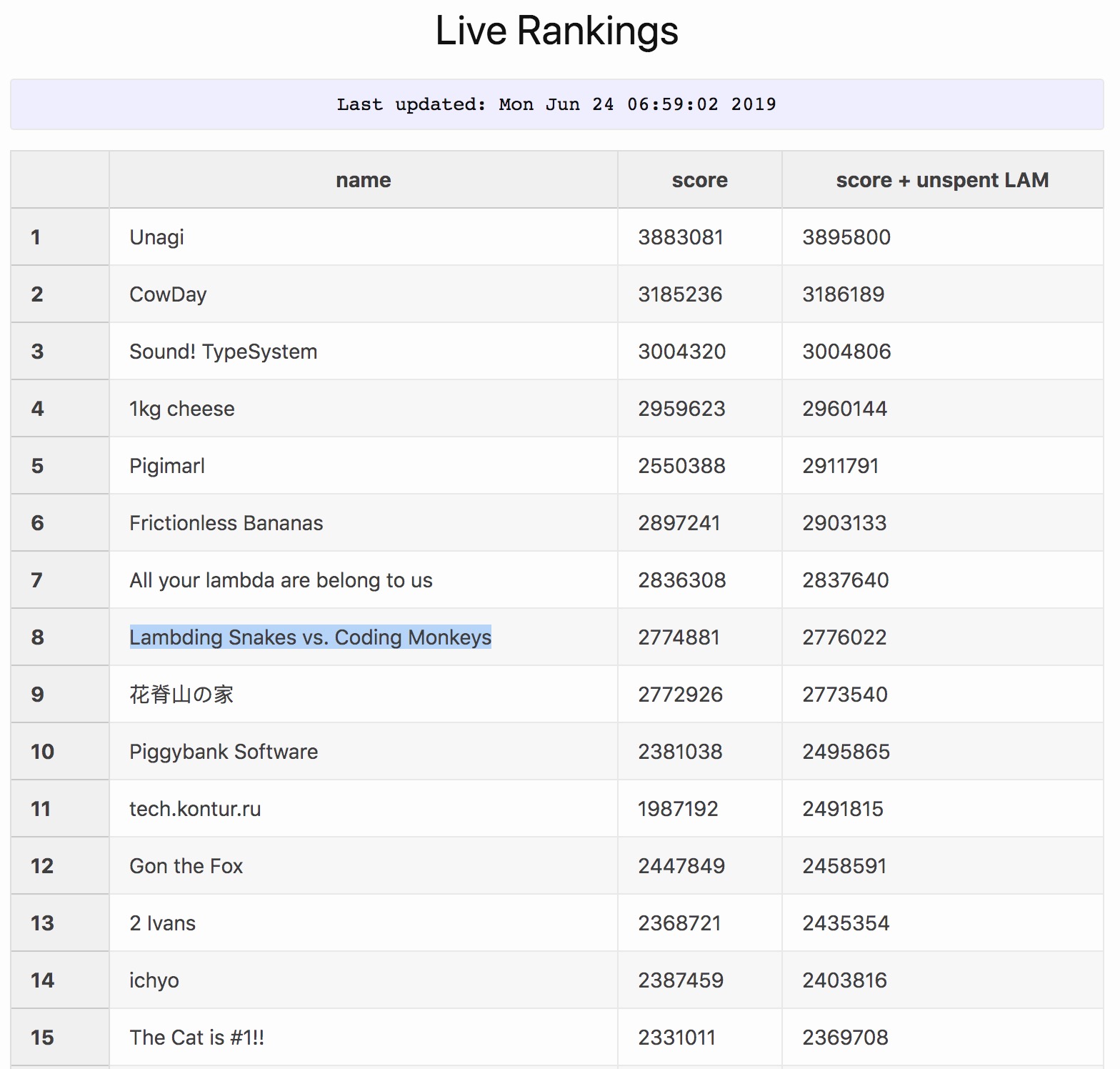

Main round

In frozen results we finished at 8th place:

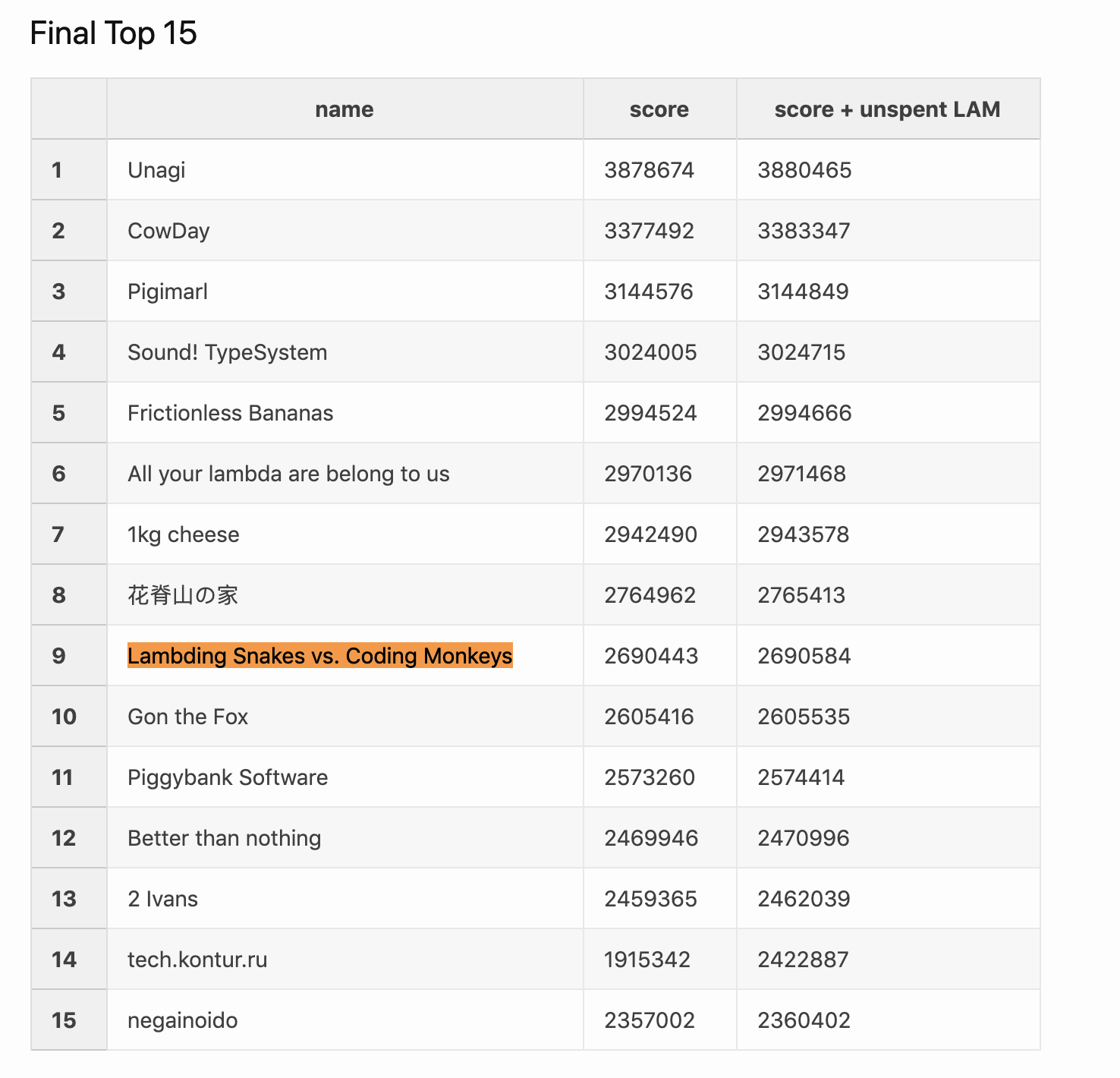

UPDATE: in final results we finished at 9th place:

Overall impression

- Contest was awesomely well organized!

- Organizer’s infrastructure worked well and without a glitch

- Timely updates and clarification

- Giving just 4 hours before the mining starts seemed too low, but this was promptly fixed

- There was live leaderboard. Competing when seeing you up-to-date rank is always more fun!

- Sadly, initial problem looked fairly straightforward and too similar to the previous year’s 3d printing.

- But change of rules in the end of lightning round brought new subproblem with blockchain exchange and new dimension for optimization, which was cool

- I personally don’t like when the rules are being changed in the middle of contest.

It’s more exciting to discover new aspects in the problem itself (for example, in “Origami” task teams

were sending more and more complicated problems that you had to figure out how to solve)

- But this year it was okay as the change of rules was only limited to lightning round.

- Interactivity layer with lambda-coin exchange was quite fun.

- I was actually expecting the problems becoming significantly complicated over time and our original

solution requiring significant redesign. But our original algorithm was able to generate all the levels.

- I guess generating hard puzzle specs wasn’t the main focus for contest, so organizers decided not to add additional twist to it

- [old man’s rant] Overall it’s concerning for me that the problems are becoming more and more about search in unbounded space, heuristics and optimization of that. There is less of obfuscation, virtual machine implementation or other things we liked previous years so much for. Like in “Pacman” year the big deal was in writing compiler/converter from regular programming language to their isoteric one. And I am not talking about “Cars and Fuels” where the whole problem was centered around figuring out what the triplet format means.

About the Team

- Team name: “Lambding Snakes vs Coding Monkeys”

- This is a fusion of our original team names when me (“Snakes vs Lambdas”) and Oleg (“Coding Monkeys”) started participating together

- Team size: 6

- Our team was distributed between 2 locations: SF (3) and LA (3)

- Programming Languages used:

- C++ (main algorithm)

- Python (puzzle generation, submission scripts)

- bash (glue, periodic tasks)

- Tools:

- git + github (source control)

- make (C++ compilation)

- slack (communication)

- 32CPU/64Gb server (computations)

Wrapping

The part of our team who was responsible for the wrapping part was sitting in other location, so I only know a few details here.

On the high-level we have a number of different strategies that were evaluated for the map and then the score from the best was used. Some of those strategies were based on the sam algorithm, but with different configuration (such as which manipulators to prioritize, what heuristic to use for next cell, etc)

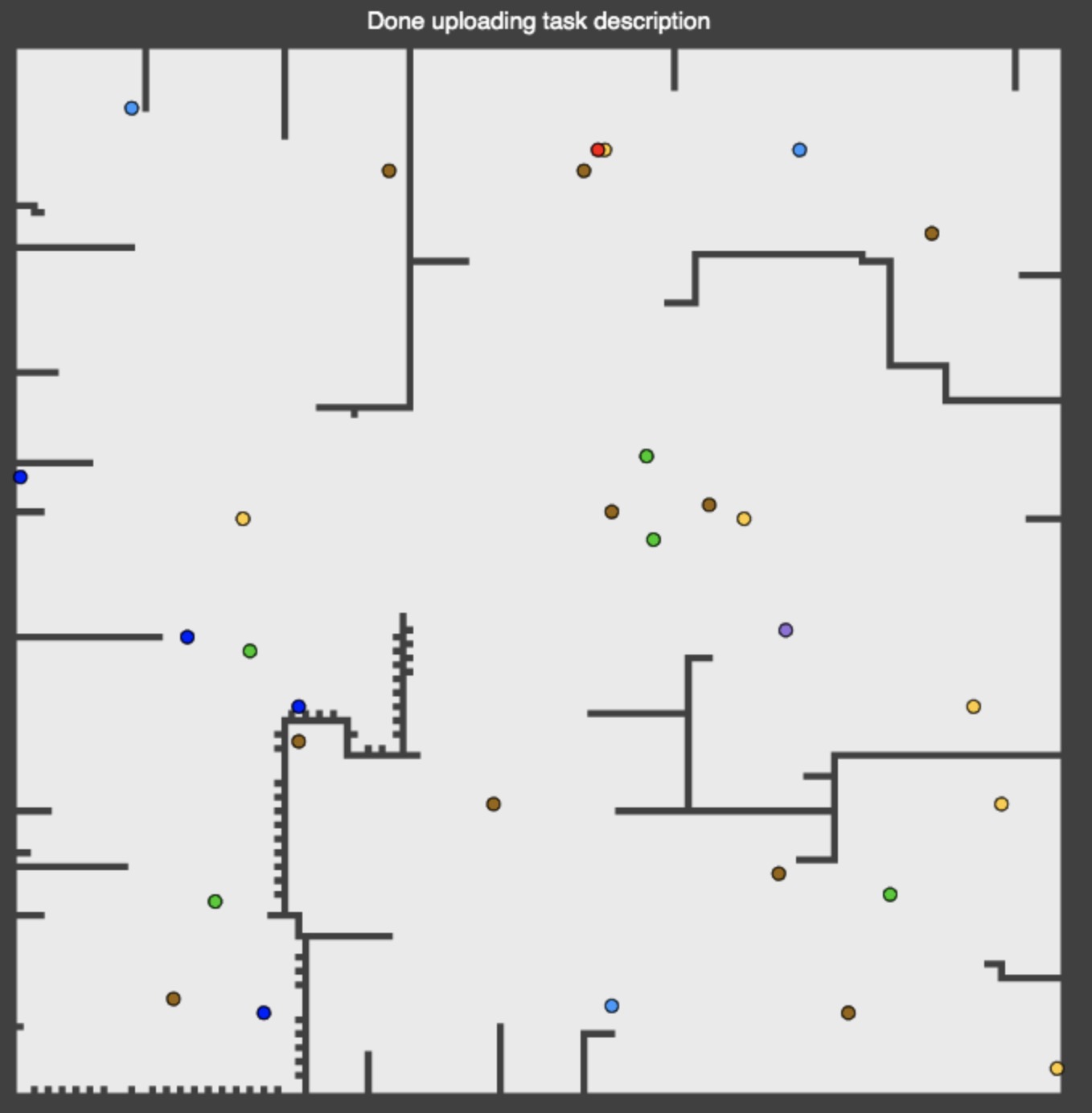

We found that among all extensions clones could provide the biggest impact so we prioritize implementation for them. The clones strategy was dividing the area into regions and assigning them to workers.

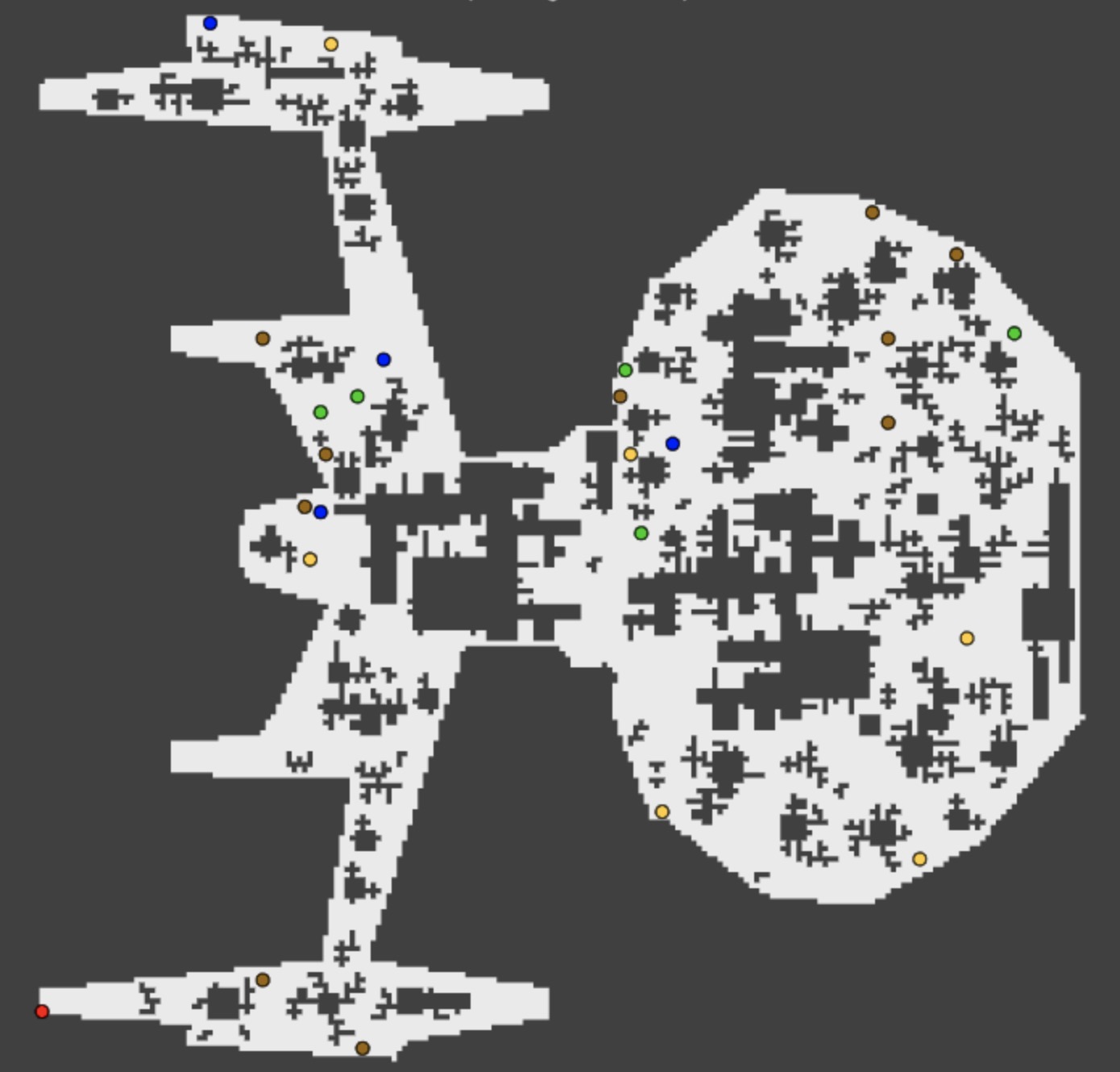

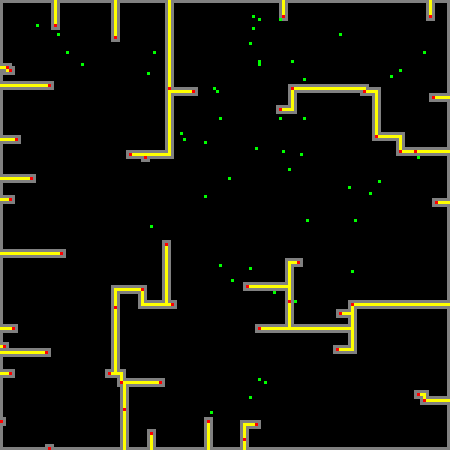

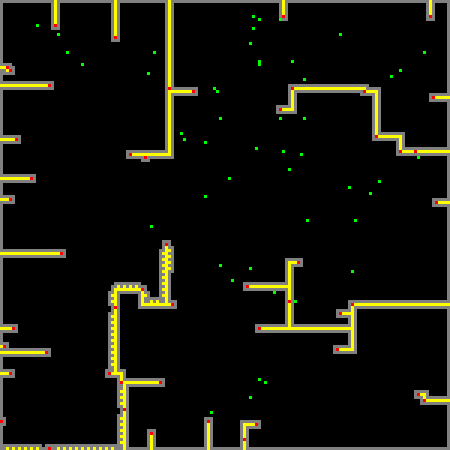

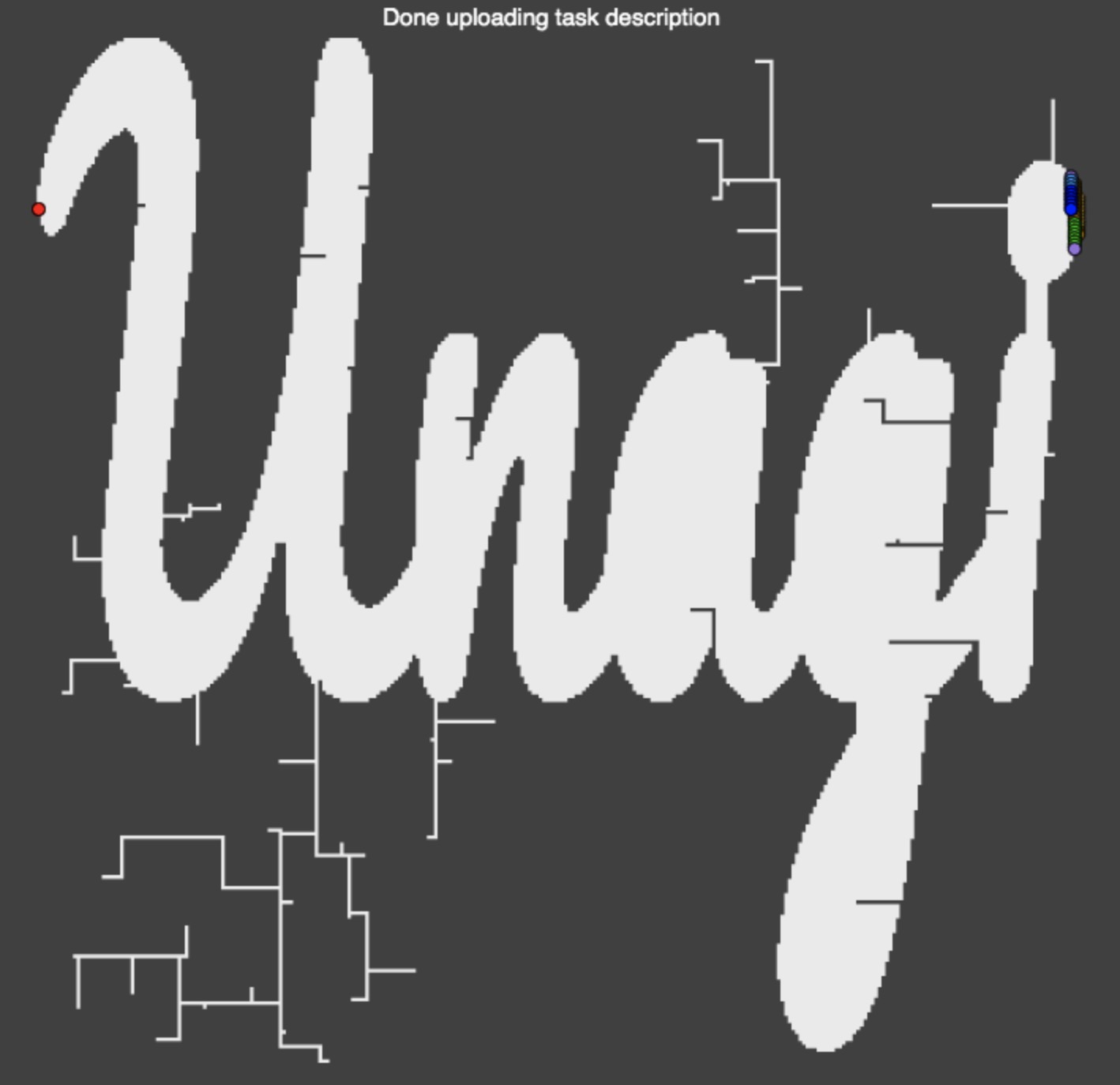

Here is the example of our submission for task 68 with buying 2 clone boosters:

Mining

The main difficulty here was to generate a map based on puzzle specification. For solving a given task we would just use wrapping algorithm from the main task. As we were around top15 teams, we would almost always get good scores.

It wasn’t clear how the puzzle spec would be changing over time, so we decided to go with the simplest algorithm and then iterate if needed:

- Sort all bad points by hamming distance from the border

- For each of them run BFS until reaching the border or the path from the previous point (yellow)

- Treat the rest of map as the internal of polygon

- Use right-hand maze rule to traverse the border (black) and generate the answer (grey)

- This algorithm satisfies almost all the required properties

- All the good points would be in one connected component

- Area would be quite large

- We additionally put all boosters randomly on the map

- Only number of corners would be too low

- Increase the number of corners by adding 1-pixel yellow “hair” to each 3+ pixel straight edge

- Repeat until desired number of corners met

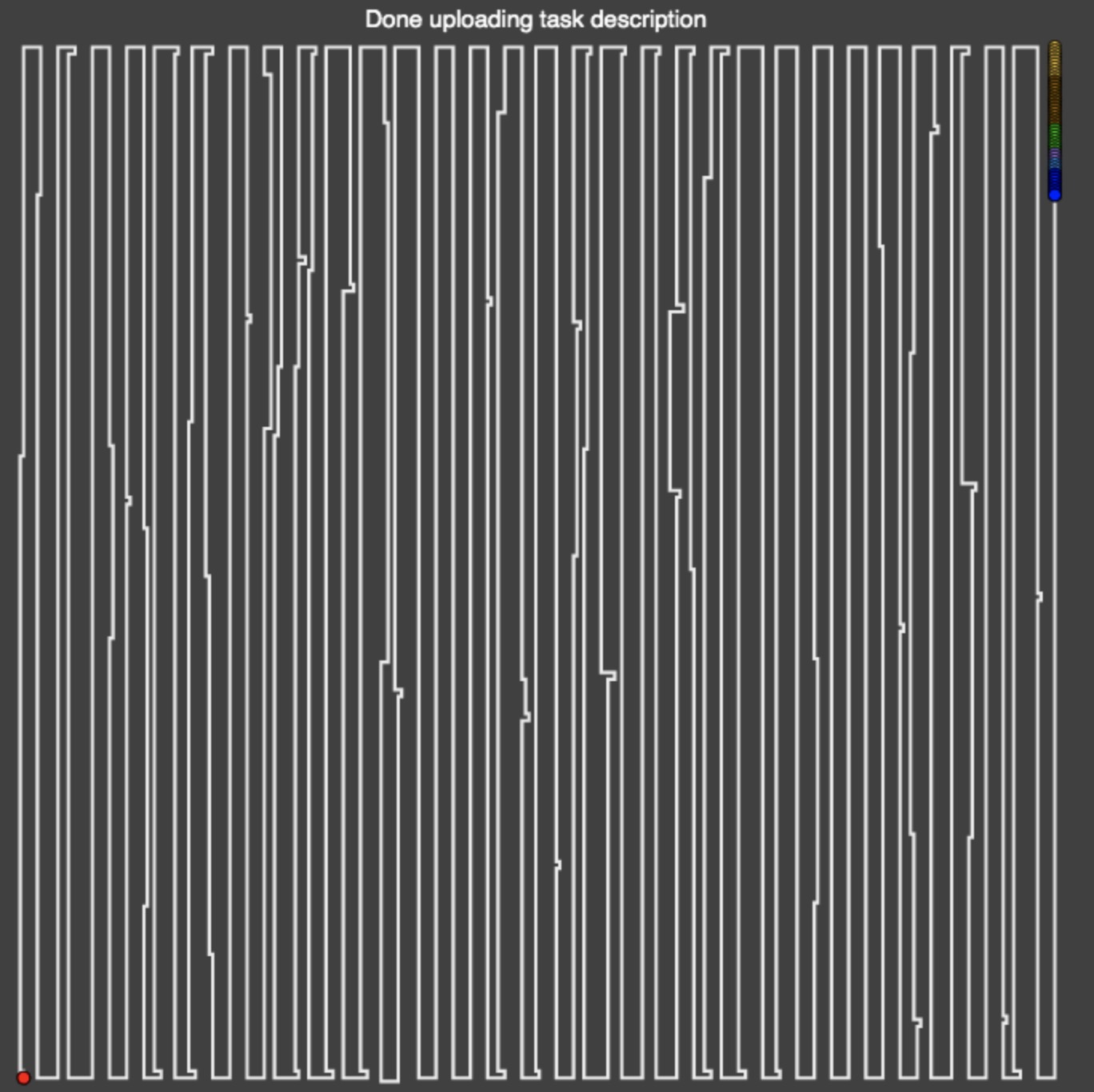

The desired map is everything inside the traversed contour:

As for the mining we had micro-services infrastructure implemented via busy loop in bash that did the following:

- commits all previously solved problems

- compiles the latest wrapper solver version

- starts the new

miner.pyprocess if it wasn’t running for some reason

ps_out=$(ps fx | grep miner | grep -v grep)

if [[ "${ps_out}" == "" ]]; then

cd ../lambda-client

./miner.py &

cd -

fi

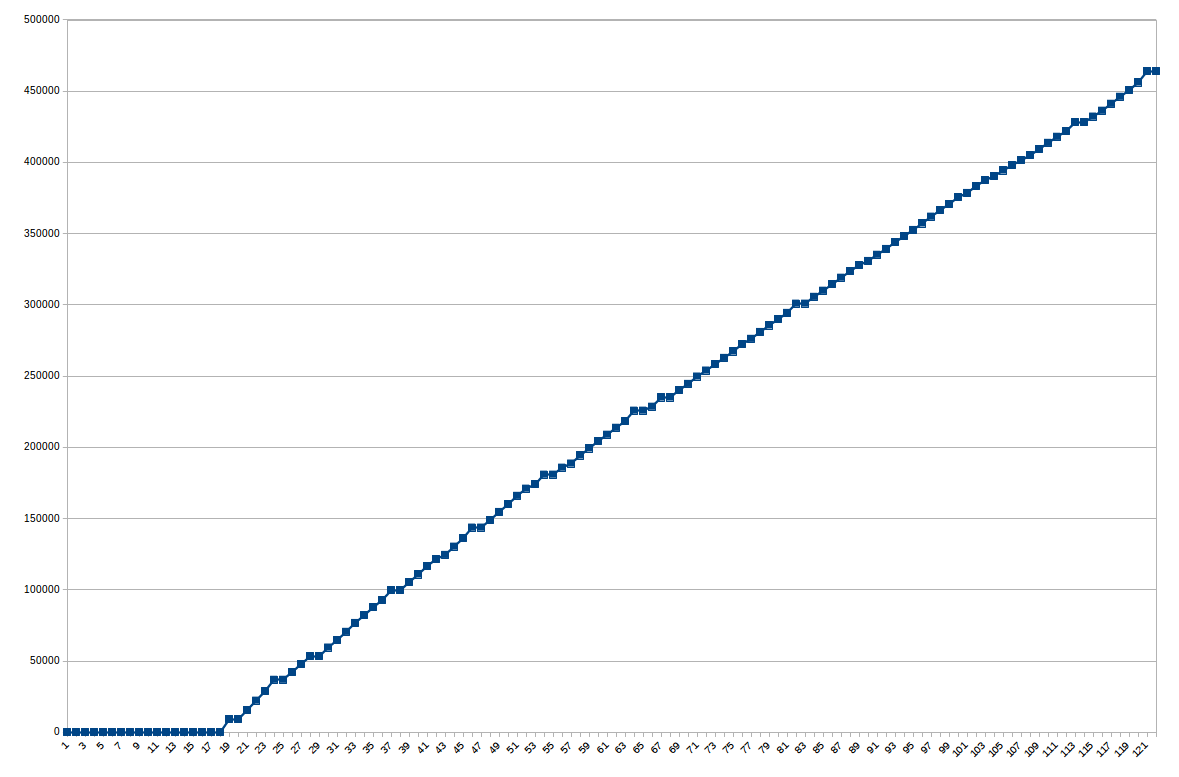

We spent quite some time implementing and debugging map generation algorithm, so we missed first 20 blocks, but then got a steady stream of lambda-coins mined

We also missed a few blocks in the middle due to the bug in our algorithm when generating contour of the polygon internal area.

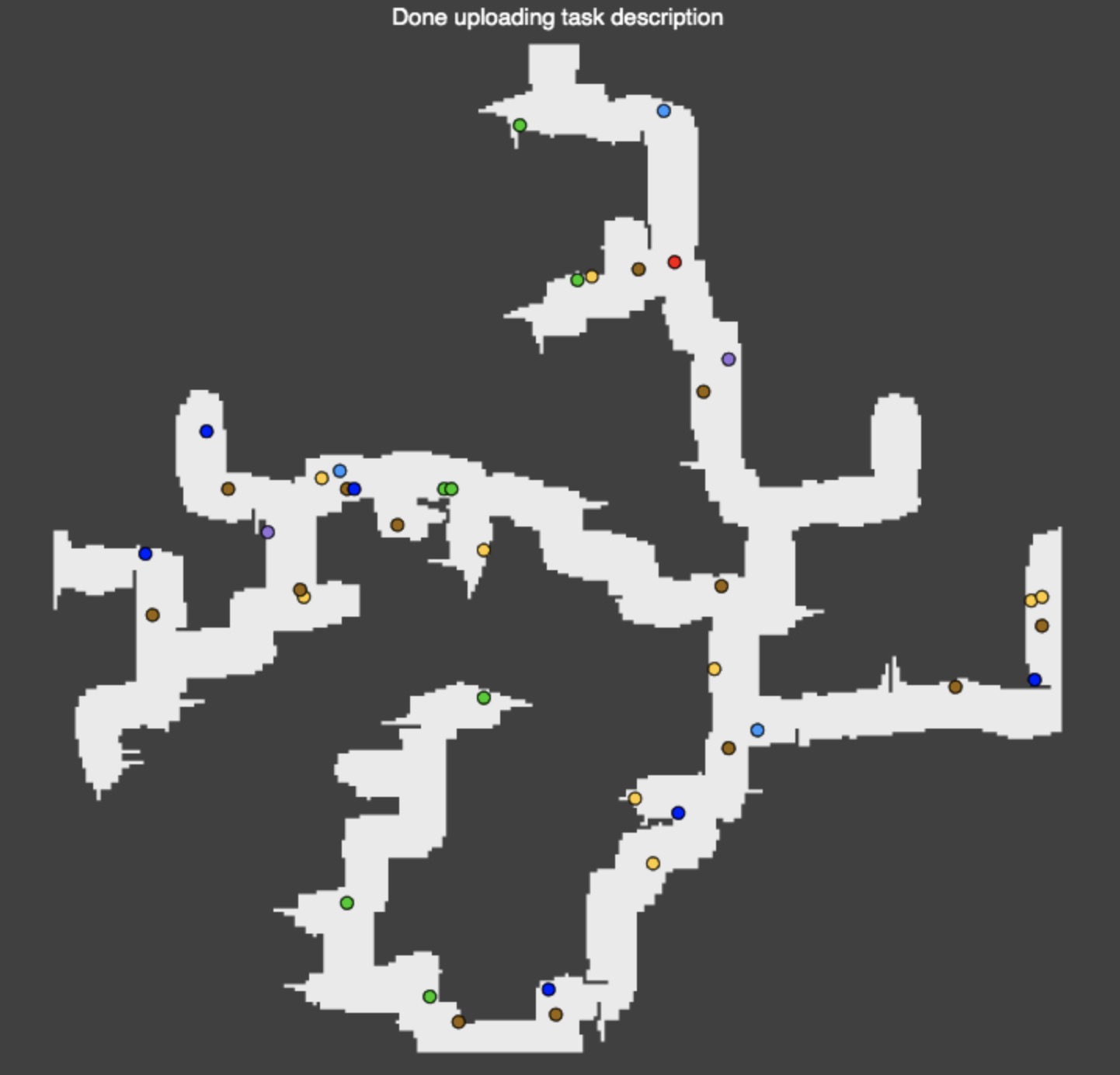

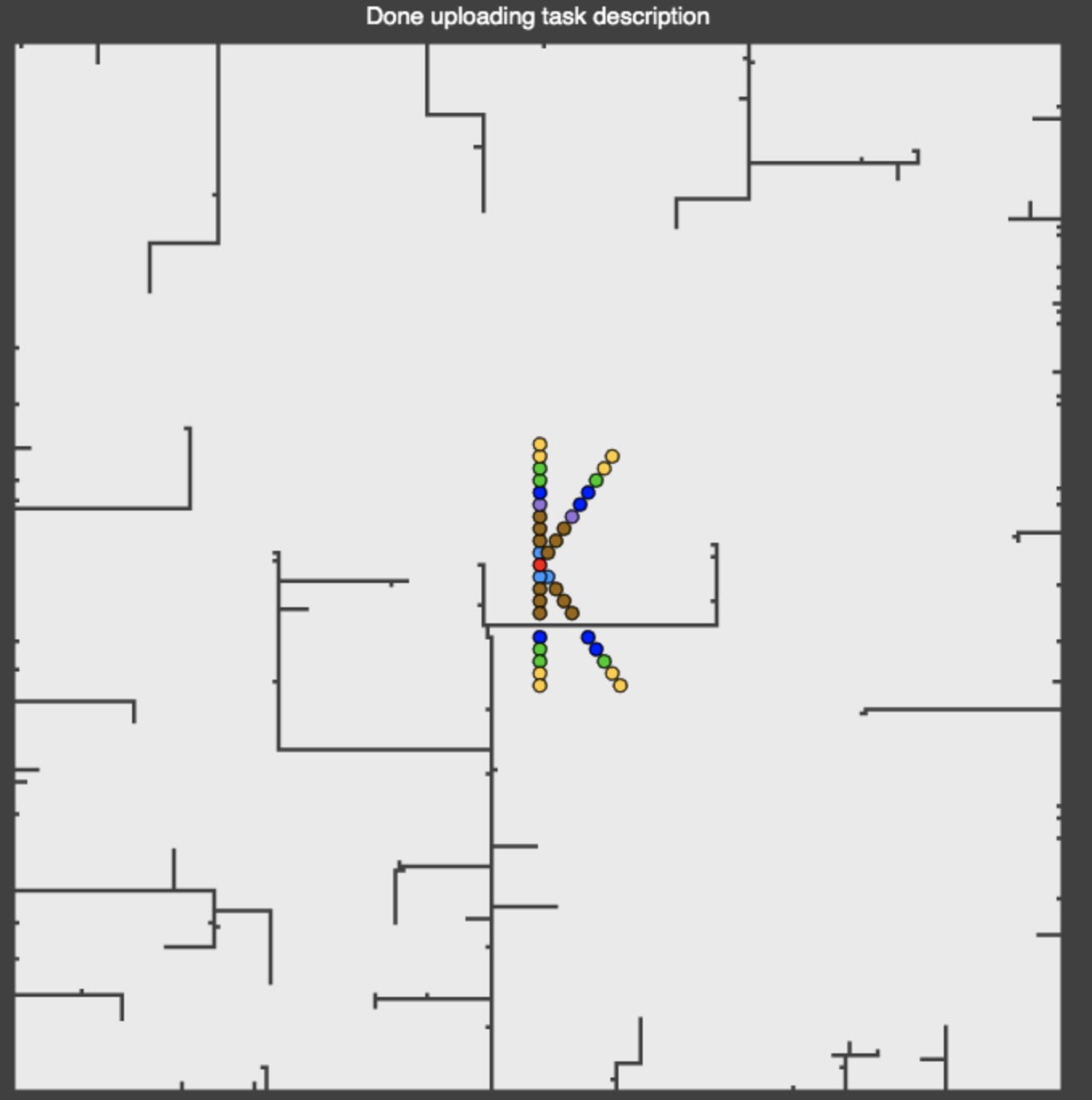

Here are some other interesting approaches that were among generated blocks:

Buying

Once we mined lambda-coins, it was time to figure out ways to use them. For us the most efficient booster was using clones, so we started running our algorithms on all maps with different numbers of clones. (our algorithms could use extra manipulator as well, but this wasn’t showing any gains, so we abandoned that).

We needed to have a way to keep track of all possible combinations and their scores, considering that algorithms could get worse and we wanted not to loose associated previously good scores.

For storing solutions we used our own buy_db database implemented via file system:

buy_db/

|---- task1/

|---- task2/

|--- 1.meta.yaml

|--- 1.sol

|--- 1.buy

Basically, the buys optimizer was treating solvers as black box and feeding various booster options,

evaluating and appending results into db together with metadata.

Then, on top special scripts could provide analytics or selection of best solutions

(see best_buy.py section)

Once we had a new score with boosters for a problem we could compute ROI. We used the following formula:

delta_score = (old_time - new_time) / old_time * max_score

roi = (delta_score - spent) / spent

As we didn’t have a way to find what’s the best time for a problem is, we used assumption that

new_time would be close to best_time, so we used approximated ratio of best_time / new_time

to be 1 for simplicity.

Then to decide how to actually spend all the lambda-coins, we sorted

all the solutions with boosters we had by incremental ROI

(what’s the incremental gain if using n+1 clones, compared to using n)

and were picking them until the budget allowed.

We have a simple UI that shows all our submissions and their ROI here.

Tooling

submit.py

Trying to learn from previous year’s lessons, we decided to invest time in a good way to keep track of final solutions.

Script submit.py is responsible for submission and persistence of the best known “pure solution” (i.e. solution without purchasing boosters). Best solutions are stored in solutions_gold to ensure no breaking changes will affect final solution.

Script compares new solutions with gold ones, does client-side validation if necessary, creates zip file with combined best known set, sends it to the server. Then it parses html response, and waits in busy loop (sorry, we didn’t have better API available) for test results. After server validation we’re updating gold solutions and gold archive if there are good updates we can store.

best_buy.py

Script best_buy.py is responsible for merging pure solutions with list of solutions with purchased boosters.

It uses greedy knapsack approach based on empirical ROI formula described above.

As soon as we’re spending less lambdacoins than boost we gain, we should be good to use.

As well as submit.py, this script ensures we’re storing “safe” solution in dedicated directory.

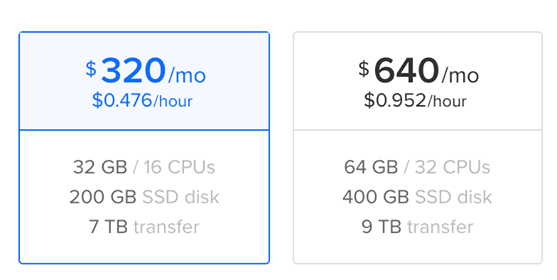

Cloud infrastructure

Our friend had a free coupon for $80 worth of dedicated servers on one of the cloud hosting provider. And the biggest machine they have with 32 CPU/64 Gb costed less then $1/hour, so we just allocated that for the whole duration of contest.

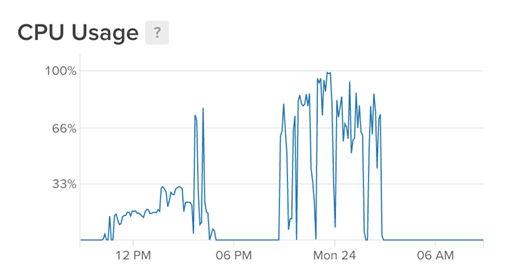

We actually started using it only towards the end of contest:

I guess we could allocated a few more for smaller duration instead. But this would be more awkward to manage and actually the computation resources were not really the bottleneck (we could re-run all maps for 20 minutes).

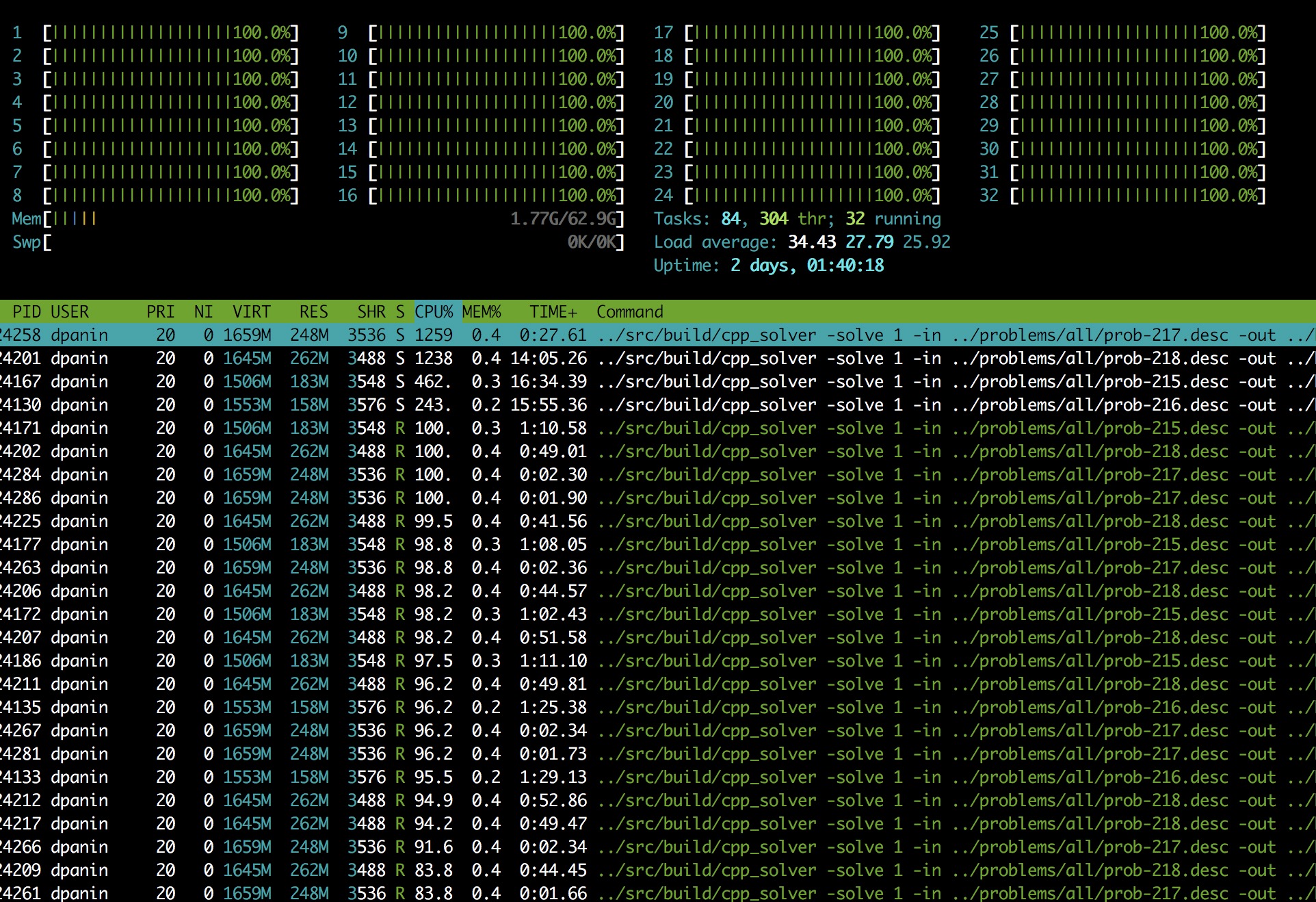

We had 32 cores on the serves, but only 10 different single-thread algorithms, so this wasn’t enough to fully load the server on 1 problem. The easiest trick to utilize server efficiently was using sharding. Each solver process has 2 command lines arguments, its shard and total number of shards. It just skips the tasks from other shard. Then we could start all of them in parallel from bash:

for i in `seq 0 2`; do

echo "starting $i"

./buys_solve_many.py $i 3 > buys.${i}.log &

done

wait

Here is the screenshot of the server happily using all of its 32 cores:

Slack bot

Integration with slack was developed as a way to monitor the progress of mining.

Also I added sending of special message with @channel (or actually <!channel> when using API)

to get push notification when the things go south.

Later on, just for fun, I implemented log_ranking.py script that was parsing leaderboard and sending

our position to slack every couple minutes.